Dear Fashion Industry: You Suck, but So Do We

Kate Casper

In late October 2019, Forever 21, one of the top fast fashion retailers in the country, announced it would be closing over 100 locations in the U.S. alone. The announcement was met with excitement from environmentalists and proponents of sustainable fashion–as well as excitement from young girls getting ready for the anticipated doorbuster sales. But what exactly goes into that $4 t-shirt or $6 pair of jeggings? What goes into your favorite pair of tennis shoes? What goes into that homecoming dress you wore only once? What is the dirty little secret that fast fashion companies like Forever 21, Zara, H&M, Nike, Pacsun, and Under Armour are hiding in plain sight? And most importantly, what can we do about it?

In an age of Insta-activism, it seems caring about the environment has become a personality trait…because using metal straws and posting about the Australian wildfires must make you super “woke”, right? The truth is, the quest to a more sustainable world is not forged by those who post; it is forged by those who act. Social media advocacy can be helpful, but it is only a small piece of the puzzle. It is personal responsibility, decision-making, and voting with your dollar that can have a lasting impact.

Fast fashion is the production of cheap clothing, often in unethical poor working conditions in developing countries. Women and children specifically are exploited in this industry, as factory-owners exercise harsh control over them. Factory owners rape, assault, and abuse workers with little consequence due to the lack of human rights regulations in these impoverished countries.

While the fast fashion industry has been exposed time and time again for its immoral, wasteful, and unethical business practices, people continue to purchase from it. This high demand for cheap trendy clothing is most likely a result of the rise of materialism in the developed world.

The theory of consumptionism states that anything can become disposable, even when it was not previously. Remember hankies? Now they are called tissues, and you throw them away. This same concept goes for clothes, as there are now 52 seasons per year in the fashion world. This means a t-shirt is not just a t-shirt–it is a t-shirt for a very specific and very limited time, and H&M thinks you need at least seven.

“I was fully entangled in the fast fashion system…I felt the pressure to refresh my closet with new ‘in style’ clothes from popular brands almost every season,” said co-founder of Students for Environmental Action senior Riley Casagrande. “I’ve shifted my habits in a few ways. The first is simply to buy fewer clothes. I have plenty of clothes in my closet, and so instead of buying new items each season, I find new ways to wear old clothes.”

This minimalist practice of consuming less is not a difficult feat, especially when for hundreds and thousands of years prior to the rise of fast fashion, humans lived comfortable (and fashionable) lives without an overwhelming amount of stuff.

However, with the emergence of haul videos on YouTube that promote a “more-is-more” ideology, apps like Instagram and VSCO that favor trend-driven highly-stylized content, and the cultural stigma projected by celebrities around rewearing things, Generation Z and Millenials have been groomed to be materialistic. Consumerism is not just chipping away the core of society, but it is degrading our earth.

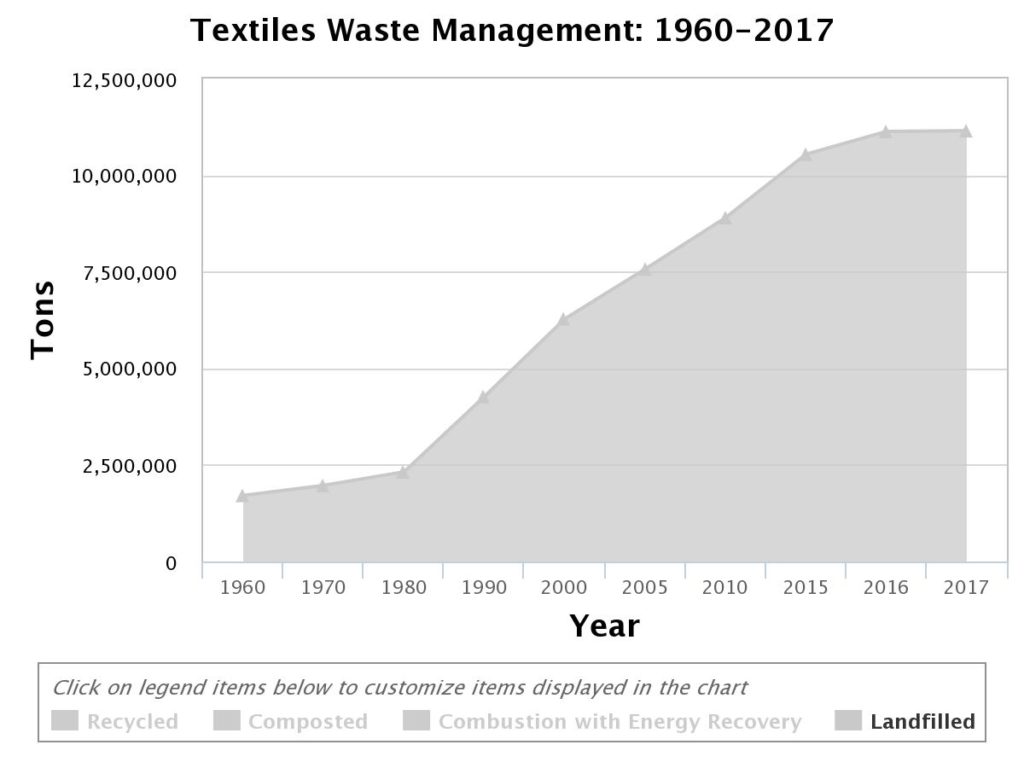

This disposable nature of garments is the reason there has been a 400 percent increase in consumption of clothes since two decades ago. It is the reason why 97 percent of American clothes are produced overseas.. It is the reason why 80 billion articles of clothing are bought per year, and why over 13 million tons of clothing are in our landfills.

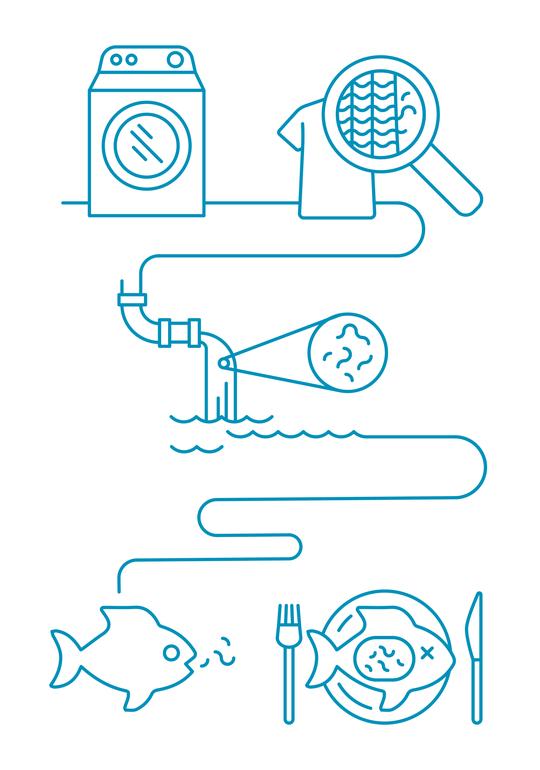

With 60 percent of the world’s clothing being made of polyester, it is no wonder this cheap petroleum-based fiber has a devastating impact on the environment. Polyester is not biodegradable, which means that when your 100 percent polyester athletic shorts are produced, they are here for good.

Every time a polyester garment is washed, hundreds of microplastics are released, infiltrating our water systems. Microplastics are then fed on by aquatic life.. By 2050, a study shows that there will be more plastic in the ocean than marine life due to the large amount of microplastics and post-consumer plastic.

While cotton is “the fabric of our lives,” it is not the fabric of the lives of farmers and workers in developing countries. Cotton is the most pesticide-intensive crop in the world. In Punjab, India, dozens of people in small villages have birth defects, severe mental illness, cancers, and other health issues due to exposure to pesticides. While farmers go into tremendous debt purchasing pesticides from big corporations like Monsanto, its parent company Bayer, profits off of pharmaceutical drugs that cure or treat the illnesses caused by pesticides.

There have been over 300,000 farmer suicides since 1985, which would make India the location with the largest wave of suicides in the world. These debts to large companies could be one cause of these deaths.

Another one of the most environmentally straining and ethically questionable materials is leather. About 80 percent of the Earth’s leather is produced using Chromium, a cancer-causing chemical. Toxic tanneries where leather is made are causing water pollution, as over 200 tanneries are producing 7.7 million liters of liquid waste per day. This Chromium-saturated waste water is getting into water systems, which can have devastating effects.

Boycotting all polyester, cotton, and leather products is impossible, but being more conscious about purchasing new clothing of these materials is not hard, especially when there are fantastic alternatives like hemp, linen, organic cotton, TENCEL®, and polyester materials made of recycled plastic bottles.

In addition, environmentalist innovators are offering more and more solutions to help resolve these issues. For example, the Cora Ball is a laundry ball that catches 26 percent of microplastics that would otherwise go down the drain.

Along with the catastrophic environmental impacts, one must seriously consider the devastating violation this industry has on human rights. In 2018, almost every clothing store in the mall sold feminist t-shirts; but, what most consumers neglected, is that the making of those t-shirts was the opposite of feminist.

Every day, women work in sweatshop labor conditions with unhealthy working environments and long hours for little pay. Factory owners undercut workers to fulfill massive orders for major fast fashion labels, often sacrificing the well-being of their employees.

In 2013, a sweatshop in Rana Plaza, Bangladesh collapsed. The conditions were so poor that the owners did not listen to worker’s concerns about the apparent structural problems. Because of this, over 1,000 people died in the building collapse.

Rana Plaza and other tragedies like it are not at the hands of the faceless fashion industry–the blood is on our hands. Because we think there is something democratic about buying a $4 throw-away shirt from Forever 21. We are enabling this.

So, what can we do?

Brands like Reformation, Everlane, Pact Organic, Patagonia, Outdoor Voices, Boden, Vetta, and People Tree are promoting transparency in the fashion industry by going on the record about working conditions, ethically sourced materials, and saving energy and water in the production process. This is transparency that goes beyond a “sustainability” tab on a fast fashion company’s website. These brands also strive to provide high quality clothing in classic styles and silhouettes that will never go out of trend and will last years.

Unfortunately, ethics and sustainability come at a cost, a high cost that even the “wokest” individuals can not always justify. This is why second-hand shopping is the most realistic and impactful solution.

A huge fan of thrifting, senior Lila Arnold started second-hand shopping in middle school. Over the years, she has found many unique pieces like a strapless plaid dress originally from Topshop or a Tommy Hilfiger puffer jacket. She said, “With thrifting, you find clothes that nobody else has, while with fast fashion you might find yourself wearing the same clothes as three other people.”

Sophomore Eli Conger said, “I thrift primarily for the experience…the unbeatable prices, distinct and exclusive pieces, and the positive impact it has on the environment are just a few of the countless benefits.” Conger said his favorite thrift find was a pair of Lee jeans that fit “unreasonably well.”

Casagrande said, “By refusing the support fast fashion brands and keeping old clothes from going to the dump, buying second hand is can have a huge impact on your environmental footprint.” In addition, her club is planning to hold a school wide clothing swap/thrift store.

The fashion industry is going to evolve–it should look like trips to the thrift store and wearing shoes until the soles rip off; rewearing your homecoming dress to winter formal; and thinking twice the next time you see a cute pair of jeans from Urban Outfitters. Unfortunately, more is more, but more is not everything, especially when “more” comes at so high a cost on our planet, people, and animals.

Now, cynics can say shopping sustainably is inconvenient. They can say that the end of the world is inevitable, so none of this matters–there is no point in trying. However, if the world is going to die, it should not have to be this painful. It should not have to look like mothers breathing in toxic fumes at work every day; It should not have to look like aquatic life consuming microplastics from our clothes; and it should not have to look like cheap clothes with loose threads and even looser morals.

Either we pull the plug on the earth, spare it and all its inhabitants of the misery we have caused, or we adapt and learn how to fix things. And that all starts with our clothes.