T.C. Hosts A Series of Speakers in Honor of Black History Month

Sadie Finn, Kate Casper, Lauren Larsen, Abigail St. Jean, and Julian St. John

Every February, 12th grade English and Drama teacher Leslie Jones and Social Studies teacher RaAlim Shabazz organize a lecture series and assembly to celebrate Black History Month. Members of the Black Student Union (BSU) also coordinate and gave presentations as well.

The two put in enormous amounts of work into these events as they host speakers, rehearse for assemblies, and make presentations. Jones also helps the drama class prepare for their performances as part of the Black Excellence Show.

Shabazz often says black history is American history and that it should be learned about in congruence with the larger story of this country. Let’s take a look into the lecture series given my many presenters as part of this year’s black history celebration.

Speaker: Dr. Deborah L. Tillman

The first in the Black History Month series of lectures was given by Dr. Deborah L. Tillman, star of Lifetime’s “America’s Supernanny” and author. Self-proclaimed child developer and parent educator, Tillman travels the country speaking at schools and having conversations with prominent talk show hosts like Steve Harvey.

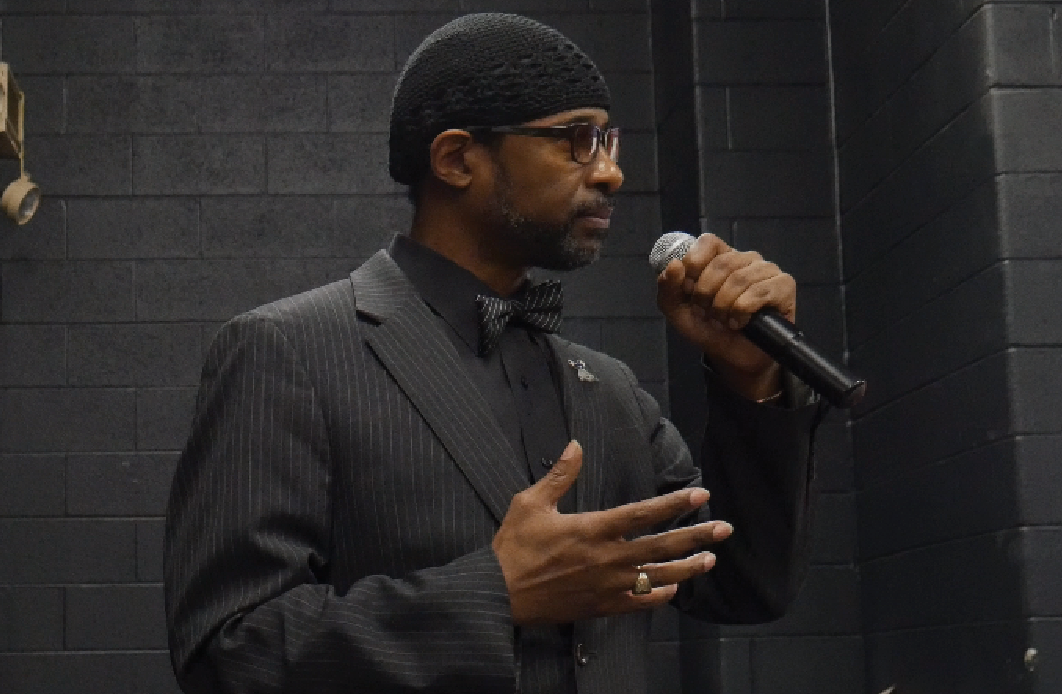

Social Studies teacher RaAlim Shabazz started off the presentation by introducing both Tillman and the greater activities going on for Black History Month. “There is a term,” said Shabazz, “In Swahili that means ‘all pull together,’ and that word is ‘harambee.’”

When Tillman took the stage, she started by engaging the audience. She asked them to turn to their neighbor and say, “your life is your message,” and then turn back to yourself and repeat “my life is my message.”

She again turned to the audience to ask what they thought that meant. “What you live is what is going to teach you,” said Senior Tobias Kargbo.

Her presentation was all about taking control of your own life and destiny because “[You] have the benefit of having not gone through slavery; you have not gone throough the middle passage; you have not gone through Jim Crow; you have not gone through segregation…Guess where they left you? We are at the 30 yard line.”

“Belief starts with STRETCHING,” said Tillman. STRETCHING is an acronym, where ‘“S” stands for “Sow seeds of success,” “T” stands for “Take time to know who you are,” “R” stands for “Read and grow rich,” “E” stands for “Expect the best,” “T” standing for “Tenacity is necessary,” “C” stands for “Create your own legacy,” “H” stands for “Have an attitude of gratitude,” “I” stands for “Invest in you,” “N” stands for “Navigate fear,” and “G” stands for “Give.” This is the process she recommends to achieve fulfillment in your life and pursuits.

Finding your purpose is essential to applying STRETCHING to your life. “But how do you know your [purpose] is right,” asked Senior Iris Castro from the audience. Tillman says to make sure to pay attention to “what brings you joy and what make you cry.”

“Be who you are, but be the best, highest version of yourself,” Tillman said. “Answer the call, answer the calling of your life. Inside every and every one of you is the scientific hands of a George Washington Carver, the millionaire mindset of a Madam C.J. Walker, the courage of a Malcolm X.”

“I know they call it Black History Month but it is really American history,” said Tillman.

Speaker: Billie Dee Tate

Billie Dee Tate is a political scientist and an associate professor at Ashford University. Tate received a Master of Public Administration degree from The University of the District of Columbia and B.A. degree in Political Science from Syracuse University. He also has a doctoral degree in Political Science from Howard University.

He led a lecture for Black History Month about the persisting effects slavery has had on Africa that he titled “Ripped From the Motherland.” This is the third year Tate has presented at T.C. for Black History Month.

He started by giving students insight on what Africa was like before the slave trade. Tate highlighted African art, weaponry, and technology. He then went into detail on the slave trade and the Middle Passage as the start of the “largest transportation of people in the history of the world. [It] depleted the most precious resource a country can have: people.”

Tate explained how slave trade lead to the Berlin Conference, a conference where European leaders met and decided to split up Africa into colonies for economic gain, and colonialism when “European nations took control of every aspect of life in Africa.” He discussed how the Berlin Conference “created artificial boundaries that separated traditional boundaries” which ended up pitting tribes against each other, creating lasting conflicts, and depriving Africans of culture and economies.

Post World War I, Tate talked about the independence movement and pan-Africanism, which he explained as self reliance and the uplifting of the African race. This led to the Pan African Congress of 1945, an attempt to bring together African leaders who “called for the end of European dominance and the subjugation of the African continent.” Tate explained that this “call for independence should have been the catalyst for independence,” but the Europeans did not listen. The Lagos Plan of Action and the Final Act of Lagos then came as a result, which encouraged organization of the African Continent.

Tate also discussed neocolonialism and structural programs that exist in Africa today. He explained that loans with high interest controlled by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) dictate the economic policies of most African nations. If the loans are not returned, countries face intense sanctions. To explain Africa’s current situation to teens, he compared African countries’ profits to a student’s paycheck and European countries to the child’s parents. He asked students if they would be able to sustain themselves if their parents took 80% of all their money earned. The current loans keep countries from putting their money into their own governments and projects like infrastructure which are essential to development. This is why 50% of people in Africa live below the poverty line. Tate believes these heavy loans by European countries controlling the World Bank has made African growth stagnant.

Tate ended the lecture by reminding students, “underdevelopment in Africa is not a recent or new phenomenon.” This lecture better helps students understand the problems facing Africa today by revealing their origins.

Speaker: Percy White III

Percy White III, a historian and genealogist who is also the son of a former sharecropper, presented some of his research from the past seventeen years to T.C. students. He primarily discussed the burning and bombing of the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921.

White revealed the truth behind the burning of the “Negro Wall Street,” coined by Booker T. Washington. “It was not a riot,” emphasized White, “it was murder.”

The Black Wall Street of the Greenwood District served as the commercial, cultural, and residential hub for 11,000 African Americans, as they were forced to live on the other side of the railroad tracks from the white people who lived downtown.

Despite the state government allowing such segregation, the black community responded to adversity with obvious success; for example, 17 members of the Greenwood District were millionaires. Circumstances quickly changed, however.

A shoe-shiner named Dick Rowland was working downtown one day. He had to go to the bathroom, but the only one he was permitted to use was on the top floor of the Drexel Building. In the elevator on the way back, Rowland accidentally brushed past the white female operator, Sarah Page, as he was stepping out.

Page filed an assault claim against him. This soon spiraled in the press as headlines exacerbated the truth stating that he raped her and left scratches on her face. Rowland was arrested, and by the laws of the court at the time, could have been lynched. At this point, even Page tried to retract what she said, but by then the damage had been done.

Outside the courthouse, up to 2000 angry white people demanded that Rowland be handed over. Over the course of the next few months, more wrongfully accused African American men were imprisoned solely because racial tensions were high.

During an armed white mob’s demonstration, a group of armed black men from Greenwood arrived. When asked to leave, the men did, but on their way from the courthouse, one of the white men tried to take a black man’s gun from him. Shots were fired and fighting ensued.

The situation intensified as white people burned the homes and businesses of the Greenwood District. Not only that, but they shot every black man, woman, and child they saw, sometimes with guns given to them by city officials.

Some of the men of Greenwood decided to put on their World War I uniforms as a symbol of respect for the U.S. since they had fought and risked their lives for the country just like white soldiers had. They were still shot and killed.

By the end of it, 1200 homes were burned, 400 people were homeless, and over 1000 were living in tents. Every member of the African American community was either killed, wounded, or detained. All there was to remember these people by was a mass grave, but no headstone.

“Each of you are the living history of the world,” said White. He encouraged students to talk to parents or grandparents about growing up in the 20th century, and how society has changed a lot, but still remains very much the same. White said that in doing so, we can better understand history and how our everyday lives now shape it daily.

Speaker: Black Student Union on Blois Hundley and T.C. Williams

The Black Student Union hosted a presentation and forum to discuss Blois Hundley’s attempt in 1957 to integrate the all-white George Washington High School and the all-black Parker Gray High School.

Three years prior, the Brown decision in the Supreme Court case Brown v. The Board of Education declared legal segregation unconstitutional. The Court ordered states to desegregate with “all deliberate speed.” However, Superintendent Thomas Chambliss Williams, whom T.C. Williams is named for, did not enact such changes until 1971, and fired the woman who attempted.

The local chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) attended a PTA meeting at Parker Gray and encouraged members to try to institute the desegregation law mandated by the Supreme Court.

Blois Hundley, who served as a cafeteria clerk for Lyles Crouch, attended that meeting and was inspired by what she heard. She met with Williams and asked him to desegregate the two high schools, but he declined.

Despite a reputation as the best cook in Alexandria, Hundley was fired for her inquiry. News rippled throughout the city, causing so much turbulence that Williams offered Hundley her job back in an effort to calm everything down. This time, she declined.

17 years passed between the Supreme Court decision and the merging of the two high schools. But finally, despite the lack of speed, both schools came together under the name of T.C. Williams High School.

Current students are debating today whether or not our school should have a name change. Despite the controversy surrounding that, the Black Student Union as well as advisors are hosting a meeting on February 27 to promote the idea of naming the cafeteria at Minnie Howard after Hundley. They hope that this will be the first step towards honoring the true Titans.