Minority Students Address Persistent Racial Inequities in Classrooms

Bridgette Adu-Wadier

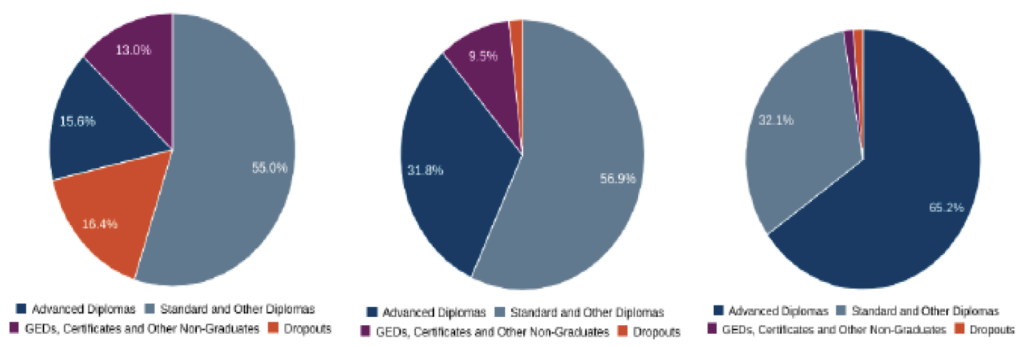

Black and Hispanic students have disproportionately low enrollment in Advanced Placement (AP) and Honors courses despite making up more than two-thirds of the T.C. population, which has sparked action among some students.

Last school year, junior Fina Osei-Owusu was the only black student in her AP World History course. Discussions on the Middle Passage were often uncomfortable for her as well, for others would stare at her.

“I was the only black one in my class. I felt like I had to represent the whole race; that is how they looked at me,” said Osei-Owusu. “AP World was a very stressful experience for me.”

Her presentation on racism in the world for her final project got an unexpected reaction.

“Most of the students just stared at me after I was done,” she said. “It wasn’t until I sat back down that a few others told me how great my project was. It just wasn’t the type of reaction I was expecting compared to how they received other people’s projects.”

This is not a unique occurrence. Junior Virginia Sacotingo was also the only black student in her AP World History course and she got stares and a sense that she did not belong.

This year, Sacotingo’s initial struggles in AP United States History resulted in suggestions that she consider moving down to general history or honors.

“I started questioning my intelligence,” said Sacotingo, “thinking ‘can I really do it?’ But I still didn’t give up.”

She stayed in the class, but even after improving her grades, struggled to get the support she needed.

“I would continue asking questions when I didn’t understand the content, but I wouldn’t get them answered. The teacher would just give me this worried look,” said Sacotingo. “When I got a low grade on the second quiz, I noticed a change in treatment. You shouldn’t treat a student differently because of the grades they get. There was a point where I felt like I had to prove myself to her, and her attitude didn’t change once I raised my grade.”

Despite Sacotingo’s and Osei-Owusu’s difficulties, data from the College Board makes T.C. look pretty good in regards to increasing enrollment of underrepresented students in AP courses. T.C. was on the College Board’s AP District Honor Roll in 2015, which recognizes schools that increased access to AP courses for disadvantaged students and raised pass rates on the AP exams. In 2015, T.C. increased minority enrollment in AP courses by 30 percent.

However, inequities still persist, making it difficult for minority students to succeed in tougher courses. The image of advanced classes being “full of white people” is also discouraging, according to Sacotingo. Controversial classroom discussions regarding race sometimes reveal biases among students and teachers and further create an unwelcoming environment.

“Recently, a student of color informed me that she had been discouraged by her counselor from taking an Advanced Placement course, with the counselor saying it might be too rigorous for her despite the fact that she had maintained an A/B average,” said Superintendent Gregory Hutchings.

Supporting minority students in advanced courses is a struggle for teachers as well, according to Sarah Kiyak, an AP English Language and AP Seminar teacher.

“The most important thing we can do is acknowledge that every student needs to be heard,” said Kiyak. “But making minority voices feel heard is a struggle. I struggle every day to recognize that I may not have given everyone a chance to speak or express themselves…I think every teacher struggles with that. And then there is the thought of ‘I have to just get through this lesson.’”

The school division will increase equity trainings for staff to help remedy underlying biases and discomfort with racial discussions. A minority student-led advocacy group, the Minority Student Achievement Network (MSAN), however, has another approach to the problem.

The T.C. MSAN students are working to teach the school what it means to be “critically consciousness,” or able to deeply analyze the systems of inequality and commit to taking action against them.

“We have to educate the entire school on critical consciousness theory,” said RaAlim Shabazz, who teaches government and advises the students in MSAN.

The club aims to generate a discussion among students and staff surrounding not just equity, but also what it means to be a black or brown student at T.C. and how they can all be better served in all types of classes, including AP.

MSAN members developed the initiative, “From Fingers to Fists” during the annual October conference in Wisconsin. There, they developed their action plan to address racial inequity by helping students and staff build consciousness.

They would start by forming partnerships with other clubs in the school such as Gay Student Alliance, Black Student Union, Best Buddies, and the National Society of Black Engineers to start educating them on what critical consciousness is and get their input.

Based on the feedback of other minority students, MSAN will come back together to create educational materials, such as a video and series of flyers, on critical consciousness to supplement teachers’ equity trainings.

“We know that the students are basically the big picture, but we know that it starts with the teachers too,” said MSAN member and junior Lorraine Johnson. “We want to be able to put our foot in the door and get out our message to these teacher in service meetings and professional development.”

Along with engaging teachers, MSAN would direct most of its energy to developing a questionnaire to research how much students know about critical consciousness. The club would then use this data to create several presentations to better educate the student body. There would also be more social media campaigns, Everyday Titan announcements and other video content to supplement the information.

Students are not usually “teaching the teachers…so [MSAN] is a great opportunity for students’ voices to be heard,” said Johnson, “especially when minorities are the majority of the population at T.C.”

Meantime, the students are working on introducing discourse on critical consciousness during the weekly community circles and classroom activities that happen every Friday. They would start with a handful of teachers that organize community circles weekly and facilitate conversations on racial inequity.

This would later culminate in a big forum for students and teachers to learn and discuss critical consciousness theory and covert forms of racism.